This is a paper I delivered at the 2014 Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts Conference in Dallas, Texas. The paper was part of a panel called “Gaming Capital,” and my co-panelists were Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux.

Ultra Business Tycoon III claims to be a port of “an old edutainment game from the 90’s,” but anyone familiar with it’s designer, Porpentine, knows that this is a feint. Designer of games like Cyberqueen (a sci-fi romp in which the player is tortured and dismembered by a computer) and Happiness Simulator (which starkly demonstrates the difficulties of being transgender), Porpentine has little interest in the typical Tycoon game. Unlike Game Dev Tycoon or Prison Architect, it should be clear early on that this game is not really interested in presenting the player with god-like powers. Porpentine’s game does everything it can to undercut the empowerment that defines the tycoon genre. Rather than managing from above and learning the processes and procedures of corporate systems, the player of Porpentine’s game is caught in a messy world of sweating and bleeding bodies. (In fact, Porpentine’s favorite subject is body fluids, making her work a perfect fit for our discussions around the theme of “fluid” at SLSA.) The game offers a framing narrative about domestic abuse, which is revealed to the player in a disorienting way. What begins as a business simulator transforms into something else. The player slowly learns that he or she is not controlling a character who is “a prominent businessreplicant in the money business” but is instead controlling a character who is controlling that character.

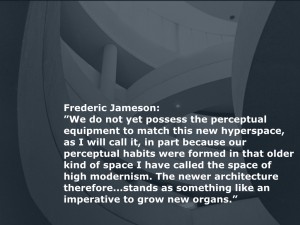

The game’s attempt to frustrate and disorient has meant that players offer mixed reviews. Some see it as a brilliant critique of the Tycoon genre, and others think that the game is too opaque to offer the kind of experience they’re seeking. Of course, frustrating game experiences are nothing new. Maybe frustration is the result of poor design, or maybe it’s an attempt by so-called art games to use frustration as a rhetorical tactic, or maybe it just reflects a game’s utter indifference to us. But Ultra Business Tycoon III is important for another reason—it offers an example of something I’d like to call “obfuscated mapping,” a strategy for understanding life in late capitalism. Or, better, a strategy for demonstrating the utter impossibility of understanding that life. If Frederic Jameson’s cognitive mapping sought a way to understand how subjects struggle to position themselves in increasingly disorienting postmodern spaces, then Porpentine’s approach to what Jameson calls “hyperspace” acknowledges the unknowability of systems (computational or otherwise) and attempts to engage that uncertainty on its own terms.

In Programmed Visions, Wendy Chun argues that the graphic user interface is a cognitive map, a direct response to the postmodern condition (a response that, she argues, might work too well by providing the user too great a sense of control). We can see videogames as the apotheosis of this form. The vast majority of games teach us that what we do makes sense, that we can control an environment, and that there is a clear relationship between actions and results. But interfaces can be designed with other goals in mind. In the remainder of my time, I’d like to consider not only Porpentine’s game but also the platform on which it was created (Twine) in terms of obfuscated mapping—attempts to map our relationship to global capital that begin from the premise that the territory is infinitely complex and perhaps even impossible to map.

Ultra Business Tycoon III

Porpentine’s game mimics the “edutainment” games of a previous era, down to the .nfo file that comes with the game.

The game begins as what seems to be an absurd take on the Tycoon genre, and the player controls a character who is tasked with, among other things, taking down corporate competitors, gaining more money, and killing anyone who gets in the way. Right from the start, we see that this Tycoon game is not exactly what we might be expecting. For instance, while we can enter a skyscraper (right in line with genre expectations), we can also choose to enter Subterranean Trash Zone II or Oasis Zone VI (where “the leylines of capitalism are strong”). Upon entering the Trash Zone, we are met with, among other things, a putrid smell and a Bee Gate. The game only gets more bizarre from here, but Porpentine’s point is that this absurd world is perhaps not much more absurd than those of games like Railroad Tycoon or Lemonade Tycoon. All of these previous examples of the genre afford the player a great deal of power as they attempt to become millionaires and rule the world. The main difference, of course, is that Porpentine’s primary interest is in holding a mirror up to the capitalistic impulse.

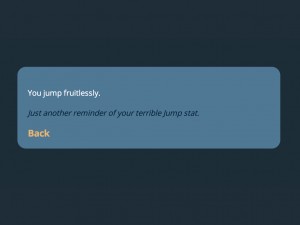

But the game’s biggest innovation (and its relevance to a discussion of obfuscated mapping) is not this direct critique of capitalism. Its most interesting feature is the moment at which we discover that this game, made in the Twine platform, has us playing the role of a player of Ultra Business Tycoon III. We get different clues about this, from humorous commentaries about the length of cut scenes to clickable text that reads “press spacebar” (pressing one’s spacebar does nothing—we must click the text).

But the most jarring moments happen when we learn that our player character lives in a dark world shaped by domestic violence. When the player character’s sister interrupts a session of Ultra Business Tycoon III, there is a tortured exchange that makes it clear that the player character does not know how to talk to the sister nor how to deal with the abuse both of them face on a regular basis.

Porpentine has created a helpless character in a no-win situation. Faced with a sister who is likely running away to avoid abuse, we can “stare at the ceiling” or tap our keyboard. But there is no option for “save sister” and definitely not one for “talk to your sister about the problem.” In these moments, we are playing two games at once—a game called Ultra Business Tycoon III and another, nameless and much more devastating game that is far more distrubing than a world of Bee Gates and weaponized potassium.

Obfuscated Mapping

The player of Ultra Business Tycoon III lacks much agency (and by “player” I mean both the person playing the Twine game and the in-game character playing Ultra Business Tycoon III). There are often no clear links between player actions and results, something that runs counter not only to popular videogames but also to the GUI designs with which most of us are used to working. Wendy Chun has argued that such GUIs should be seen as examples of Jameson’s cognitive maps, designed to respond to the postmodern condition.

Stepping through how Douglas Engelbart’s NLS and Vannevar Bush’s Memex have informed contemporary interfaces, Chun demonstrates how the GUI puts “us” in the driver’s seat. This becomes especially clear in Engelbart’s “mother of all demos”: “Through our identification with Engelbart via his demo we emerge as sovereign subjects—subjects of files. Not accidentally, Engelbart’s tasks are administrative: compiling lists, assigning ownership to files” (85). As Engelbart copy/pastes and clicks with his mouse, he is in control, and his face melts with the screen to demonstrate how he is the one navigating this space. Command and control is coded right into the design of the original GUI, and this megalomaniacal user reaches new heights in a number of contemporary videogames, as players expect to be in a position of control.

Of course, Chun also argues that this is a fiction, that computers are demonic, always “inhabited by invisible, orphaned processes” that run in the background, often completely out of the user’s control. In a response to this lack of control, Chun argues, we actively work to forget that our interfaces are maps. Instead of seeing them as representations, “we try to inhabit them, and, by inhabiting them, we turn them into something other than a map” (93).

Instead of seeing maps as imperfect attempts, we are encouraged to see them as successes that “clear up confusion and establish the user as the sovereign subject, in control of what she sees: she controls technology that transparently reveals her relationship to the invisible laws of computation” (89). Chun’s argument is not that we need fewer interfaces or that we should abandon these attempts to map. Instead, she is suggesting that we fully embrace the idea that computers are “metaphors for metaphor” and that we engage in the practice of mapping by recognizing “the artificiality of metaphor…mak[ing] strange and estranging the world around us” (94). By embracing this approach, we could begin to see all maps as “deliberately odd and artificial” (94).

The notion of obfuscated mapping that I’m describing in by way of Ultra Business Tycoon III is my attempt to embrace the computer as a metaphor for metaphors. I am, of course, pulling the term “obfuscation” from the idea of obfuscated coding, a practice of writing unnecessarily complex computer programs. In an essay entitled “A Box, Darkly,” Nick Montfort and Michael Mateas argue that obfuscated code can both shed light on programming languages (pointing out quirks and affordances of certain languages) and can productively defamiliarize our encounters with code (10). For Montfort and Mateas, obfuscated code demonstrates that a program could be written another way, even if that other way is tortured and unduly complex. Such code reminds us that utility is but one outcome of computer programming.

But questioning utility does not have to mean alienation, and obfuscated code is strangely hospitable to those willing to take it up. Montfort and Mateas argue that obfuscated code and weird languages “invite theorists and critics of new media to look into the dark box of the machine and see how creativity is at work in there, too” (10).

While Montfort and Mateas are primarily concerned with expanding the aesthetics of code, my aim is to understand the work of Porpentine and others as obfuscated maps—as attempts to map life in late capitalism. If obfuscated code exposes the workings of a programming language and calls for reconsiderations of how code is written, it does so by way of a particularly frustrating path. Yes, obfuscated code invites interaction, but it simultaneously frustrates that interaction by making itself opaque and difficult. Like Porpentine’s Ultra Business Tycoon III (and a host of other games made in the Twine platform), obfuscated code eschews clarity in the name of complexity. In Porpentine’s version of the Tycoon game, it’s not immediately clear who or what I am controlling, let alone what I’m trying to accomplish or how I might “win” the game. Such complexity offers a much more fitting account of life in global networks of capital, which never make it clear how one can or should act and which often make it difficult to directly link action with result.

Twine: A tool for Obfuscation?

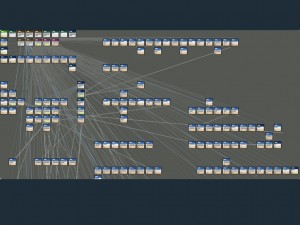

As we consider obfuscated mapping as a tactic for life in late capitalism, it’s worth considering not only Porpentine’s game but also her tool of choice, Twine. Interestingly enough, the design view of Twine, the platform used to create Ultra Business Tycoon III, presents the designer with a map of passages and links, one that puts the designer in the “command and control” seat. From this perspective, it seems odd to argue that Twine offers any kind of obfuscation. Still, even if we were to argue that Twine developers are caught up in the GUI control fantasy, this wouldn’t prevent us from considering Twine games as sufficiently obfuscated.

In a platform study entitled “Untangling Twine,” Jane Friedhoff argues that Twine’s development as a platform must be considered alongside the community that helped make that platform successful—namely, LGBTQ writers and designers. A free, open-source platform, Twine has offered the non-programmer a tool for creating and publishing text-based games. Friedhoff argues that the features of the system (it’s free, easy to use, and offers a simple distribution model) can be linked directly to the types of games we find developed in Twine. The taboo material dealt with in many Twine games would likely not be available on game consoles or Steam (though, Twine games have found their way to these spaces in certain instances). Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine a game like Ultra Business Tycoon III emerging on any other platform, but other games like Encyclopedia Fuckme bring this argument into sharper focus.

With Twine, we see how a platform and a user community are often woven together. There is a convergence between the technical affordances of a platform that relies on links and clicks and the concerns of the LGBTQ community. Twine’s focus on forcing choice (see, for instance, the scene referenced above when the player of Ultra Business Tycoon III does not really engage her sister) simulates the gender choices foisted upon those in the LGBTQ community, and the inability to escape those decisions tie that community to this platform in interesting ways. In addition, many Twine games play up a lack of player agency. A review of Twine on Rhizome puts it this way: “Twine text-based games emulate our limited agency within our daily experiences with work, lovers, friends, art, life, and as such have proven a valuable cultural form for people who, in their daily lives, must work within a limited set of choices.” The review goes on to argue that many Twine games attempt to “highlight the arbitrariness of the user’s decisions, their lack of agency.” This is especially clear in one of Porpentine’s other games, Howling Dogs, which Leigh Alexander describes this way: “Howling Dogs is an abstract, often surreal experience centralized on the concept of confinement; even though it’s a text game, it feels spatial and non-linear, as the player must repeat certain conventions of self-maintenance.”

While Twine is anything but obfuscated as a design platform, it has created a way for LGBTQ designers to create disorienting experiences that leave the player with a confusing map and, often, a diminished sense of player agency. And there seems to be quite the need for such game experiences. Consider one player’s response to Ultra Business Tycoon III:

As a game, I found the biggest flaw to be how difficult it was to know what to do when (or even if there was a “right” or “best” or even “productive” thing to do). As a story, I found it surprisingly compelling, in the same way that a kid feels about poking a dead thing with a stick. But the appeal wears off pretty quickly.

A response like this one reveals a player is so trained to see player characters as heroic that he misses the central premise of the game: That the pure, frictionless control of many games is a fiction and that the character in Porpentine’s game, hiding in a bedroom playing Ultra Business Tycoon III, feels so trapped in a spiral of domestic abuse, depression, and isolation that she can’t actually step outside of the “passive” responses that so frustrate this player. It would seem obvious that the limited options provided (similar to those offered in another popular Twine game called Depression Quest) are meant to evoke passivity. There is no saving the princess in Ultra Business Tycoon III. What’s the most ethical response here? To stare at the ceiling? But this player and many others have been trained by a range of interfaces to see this as a bug rather than a feature.

If, as Chun argues, the GUI was designed as a response to late capitalism and if that response has essentially worked too well by offering up an illusion of control, then games like Ultra Business Tycoon III might offer one possible way forward for those attempting to understand the disconnect between bodies and space in networks of global capital. Perhaps obfuscated mapping is best understood by turning not only to Twine and Twine games but to the array of practices and strategies deployed by LGBTQ writers. These writers have used Twine to describe lives in which concepts like agency and control are especially fraught, lives that offer a particularly extreme version of the vertigo and displacement many associate with late capitalism. This community (along with its tools and theories) seems the best place to turn for ideas about how to build obfuscated experiences, maps that can serve to remind us that all of our attempts to understand contemporary space are failed ones and that this can be a starting point rather than a dead end.